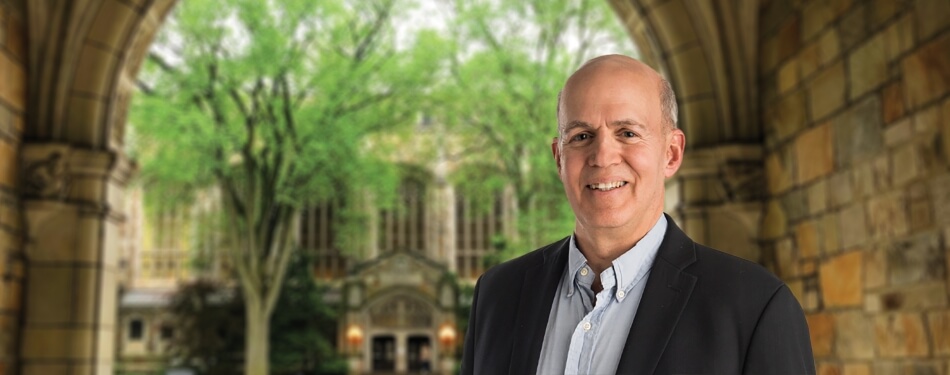

Whenever the US Supreme Court takes up a substantive case involving the Constitution’s confrontation clause, Professor Richard Friedman—one of the leading experts on the clause—typically submits an amicus brief.

Friedman’s work was instrumental to the landmark Crawford v. Washington decision in 2004, which strengthened the right of criminal defendants to demand that witnesses testifying against them be brought into court for cross-examination. He has also successfully argued two follow-up cases, he publishes the Confrontation Blog, and he has been cited on the issue at the Supreme Court six separate times.

The most recent citation came near the close of the latest term, when the Court ruled in Smith v. Arizona that the clause was violated when an expert witness testified about laboratory analysis that had been conducted by someone else. (The Court sent the case back to the state to consider a separate question, whether the analyst’s statements constituted “testimony.”)

In addition to the citation of Friedman’s amicus brief in the majority opinion—written by Justice Elena Kagan—a concurrence by Justice Samuel Alito separately cited a 1991 article by Emeritus Professor Samuel Gross. Friedman—the Alene and Allan F. Smith Professor of Law—recently answered five questions about the case:

1. What was at issue in Smith v. Arizona?

The confrontation clause has been understood since Crawford to require that those who give testimony against the accused must testify face-to-face, under oath, subject to cross-examination. That applies to lab witnesses who make a lab report that’s clearly going to be used in prosecution. In effect, if you just submit that piece of paper, you’re allowing the lab analyst to testify against the accused without facing them in court.

Some prosecutors have argued that they are not introducing the lab report for the truth of what it asserts but rather only in support of the expert opinion—which would mean the confrontation clause doesn’t apply. Rule 703 of the federal rules of evidence—which has been copied by most states, including Arizona—says that an expert may testify on the basis of information that is not necessarily admissible if it’s of the type that experts in the field reasonably rely on.

In a 2012 case, Williams v. Illinois, four justices bought that reasoning. The other five justices disagreed, saying you’re really admitting the report for the truth of what it says. But Justice Thomas joined the four on another issue, and the whole thing was in confusion. In Smith v. Arizona, the issue came up cleanly, just by itself. The question was, if the state says we’re only offering this statement in support of the opinion, does that satisfy the confrontation clause—even though the statement supports the opinion only if it’s true?

2. What was the outcome this time?

The majority said no, because the report is actually being offered for the truth of what it asserts. The majority further said that Rule 703 is an evidentiary rule, and therefore it doesn’t control the Constitution. The Constitution means what it means. The Constitution says, if you’re offering something for the truth of what it asserts, then you have to prove it through admissible evidence, subject to confrontation.

The Constitution trumps evidentiary rules, not the other way around. But they further said that if an evidentiary rule reflects long-standing practice, it might reflect the understanding of the confrontation right at the time that it was framed.

3. What is the specific point from your brief that the majority opinion cited?

They cited me to say that Rule 703 was a creation of the late 20th century, so it couldn’t be a reflection of what’s always been done in evidentiary law. Beyond that, it was understood by its drafters to be a departure from traditional practice. So Rule 703 can’t control the Constitution. I was pleased to see the citation because it was an accurate citation of my brief. It was an important point at the core of the case.

4. Does this decision provide the clarity lacking after Williams v. Illinois?

Yes, on that specific point. It’s clear that this strange end run—saying “we’re only offering this in support of the opinion, we’re not offering it for the truth”—won’t work. On that, the ruling was very clear.

Unfortunately, in my view, the Court went beyond that and discussed some questions of the standards for whether a statement is testimonial. That wasn’t really presented, but it was discussed a lot in the briefs and at argument. The Court offered some comments on that, and I don’t think those were particularly helpful. We’ll have to see what happens. But on the point that was before the Court, it was very clear and the opinion resolved it.

5. The case included another Michigan Law citation: Justice Alito’s concurrence cited Sam Gross’s 1991 article, “Expert Evidence.” How is that significant?

Justice Alito is saying that we had a deficient way of presenting evidence—relying on hypothetical questions in court—which Rule 703 cleared up, and now you’re driving us back.

There are all sorts of problems with hypothetical questions. They are subject to a lot of abuses. Sam points out a couple of them, and Justice Alito was citing him for that. One problem is that they were sometimes extremely long and confusing. Another is that they were often used in effect as early summations of the argument, and maybe sneaking in inappropriate information.

Sam wrote a great article, and the citation shows it still has legs after all these years.