During three sweltering days in July, an estimated 500,000 people visited the Ann Arbor Art Fairs. While checking out the paintings and the pottery, the furniture and the fiber art, visitors also had the unusual opportunity to contribute to legal research.

At a high-visibility booth on the corner of State Street and North University Avenue, fairgoers completed more than 1,000 surveys that will help Michigan Law Professor Roseanna Sommers and Nicholas Camp, a professor in LSA’s Organizational Studies department, in their research projects.

“Much of my research asks how people who don’t have legal training think about legal concepts,” said Sommers, an assistant professor of law who is a social psychologist and founder and director of the Psychology and Law Studies (PALS) Lab. “I try to identify areas where the law misaligns from the public’s understanding.”

All that is well and good. But why the Art Fair?

“We hatched this idea that Art Fair would be a great opportunity to run psych studies,” she said. “There would be so many people, and they would be more diverse—in terms of age, education, economic status—than the samples we typically recruit in our research.” The professors, like many experimental psychologists, largely rely on university students and online respondents for their data collection.

“I think it’s really great to do research in person,” Sommers said. “I’m not going to claim that the people who come through Art Fair and agree to be in our studies are perfectly representative of the country. But we do try to recruit a more inclusive and broader swath of people to take part in these surveys.”

The professors decided on four studies—two for Sommers and two for Camp, who examines the role routine police-citizen encounters play in building and undermining police-community trust.

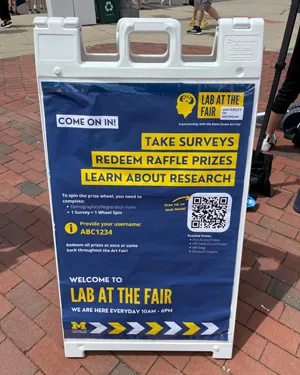

And then came the fun part: deciding how they would gather data. This involved the surveys, a spinner wheel, and the chance to win some amazing prizes (including lots of U-M swag from the M Den). The manager of the PALS Lab, Taylor Galdi, and the manager of Camp’s Mind in Society Lab, Yuyang Zhong, worked around the clock contacting local businesses about donating prizes and getting the booth ready for the event, billed as “Lab at the Fair.”

“We told people who came by our booth that one study equals one spin, so if they do this 10-minute survey, they can spin the prize wheel,” said Sommers. “It’s funny; psychologists have long known that people are more motivated by the chance to win a big prize than by a guaranteed small incentive, but what we learned was that the opportunity to spin the wheel was itself a big draw. It was fun and exciting for them.”

What do you know about Miranda rights?

Despite the novel approach, the actual data Sommers gathered was very rich.

The first of her two studies centered on respondents’ knowledge of Miranda rights: what the police are allowed to do, what happens if you stay silent, what happens when you ask for an attorney, and how clearly you must state that you want an attorney.

Sommers said there were different versions of the study, but most people read a scenario and answered questions based on that scenario.

“For half of the people, the scenario involves someone who either witnesses a crime or is suspected of committing a crime, though not under arrest. They don’t want to talk to the police, but the police are asking them questions. We asked the participants whether they have to answer the questions or whether they can walk away without answering.

“For the other half of the people, there’s a scenario where they’re in the backseat of a police car. They aren’t being questioned, haven’t been read their Miranda rights yet, and don’t say anything. In both scenarios, we asked people whether their silence can be used against them later in court.”

Sommers partners on this research with Kate Weisburd, a law professor at George Washington University who helped develop the police car scenario based on a real case involving someone who was in a car accident and then arrested and placed in the backseat of a police car.

“The police weren’t asking questions, and this person stayed silent,” Sommers explained. “Later, his silence was used against him in court because he never asked if the victims were okay, and that was portrayed as incriminating. And so your right to silence isn’t just whether you have to answer the questions; it’s also what inferences are allowed to be drawn from your silence.”

Sommers is still analyzing the data from the Art Fair, but she has some preliminary conclusions. “I can tell you already that there’s a lot of confusion among members of the public about Miranda rights, and that’s something we’re really worried about.”

Moral Dilemmas

Her other study, which centered on moral dilemmas, was more exploratory.

“I didn’t have a hypothesis,” said Sommers, who works in the field of moral psychology. “I’m really just curious to see what people wrote in response to some open-ended questions: Think back to a time when you felt morally torn. What was the dilemma? What made the decision morally difficult? What did you ultimately decide to do?”

The point was to learn what moral issues people face in their everyday lives, which could help shape a research agenda going forward. Psychologists, she noted, have given lots of attention to exotic thought experiments like the “trolley problem,” which asks whether an out-of-control trolley should be diverted to hit and kill one person in order to save five others from being hit and killed. Sommers was interested in learning from fairgoers about the sorts of moral dilemmas they personally have struggled with.

“In one of my favorite responses, someone wrote, ‘One time, I really wanted a pack of cigarettes, but I was low on cash. What made the decision difficult was that I wanted cigarettes, but I didn’t have enough money.’ In response to the third question, they wrote, ‘I stole some money, so I was able to buy the cigarettes.’”

Although the Art Fair responses more commonly involved dilemmas with friends, employers, religion, and academics, the research agenda Sommers develops could include legal questions like the cigarette dilemma and how people feel about breaking the law.

With the quality and quantity of data collected, Sommers and Camp are already planning for next year’s Art Fair.

“We are really excited to return, if they’ll have us back. We loved being out in the community doing our research,” she said, with raves for the fair organizers. “In my experience, when you approach people about collecting data at their event, there’s a real range of responses. But the State Street District said they’d love to help support research. They were excited about the data collection opportunities and the fact that so many of our prizes helped funnel people into local businesses.”

She also welcomed the opportunity to educate the public about the law.

“At the end of the Miranda study, we gave out information to people about their rights. So when they walked away, they hopefully knew more about the law than when they started.”

While you can’t spin the wheel for a prize, you can take Professor Roseanna Sommers’ surveys on Miranda rights and moral dilemmas. She will use the information in her studies.

*Banner image: LSA Professor Nicholas Camp and Michigan Law Professor Roseanna Sommers at their Art Fair booth.