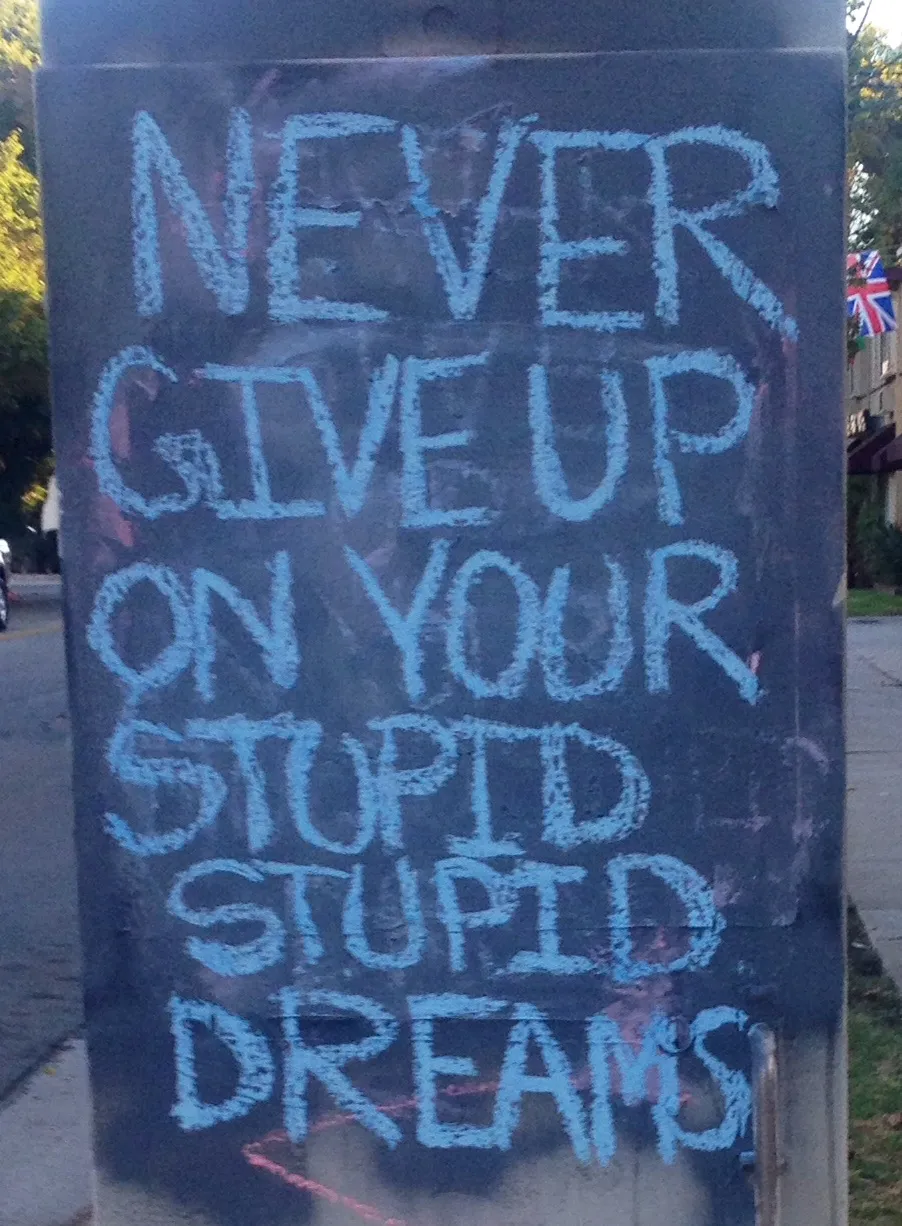

Never give up on your stupid, stupid dreams.

Not long ago I was in Los Angeles for work, taking a walk in the sunshine in order to introduce my body to the idea that it was three hours earlier than it had been five hours before, and came across this bon mot graffiti’ed on an electrical box:

Am I alone in finding this hilarious? I love the idea that someone felt compelled to share this sentiment—which may be the pinnacle of passive-aggressive advice? or maybe it’s just aggressive-aggressive—with the world. It’s so mean, and yet it definitely makes me want to say, “thankyouverymuch I think I will, in fact, stick with my stupid dreams.” Kind of a double-reverse puppeteer move, psychology-wise.

Anyway, ever since I spied that tidbit, I’ve been diligently trying to think of a way to shoehorn it into a blog post, and I’ve decided that it isn’t too much of a stretch to give some advice about advice. Receiving advice, specifically.

Because, I mean, to be honest, I sympathize with this person’s compulsion to share his/her views with the world. After all, as I have had occasion to observe, I am myself rather fond of giving advice. Indeed, one of the things I love about my job is that people will ask for my advice, which is convenient. The absence of being asked is often no impediment to my offering it, but it is nice to be given permission. Sometimes I’m asked about things I’m really not qualified to talk about (e.g., undergraduate admissions), and sometimes about things with which I have some passing familiarity (e.g., law school generally). And sometimes I’m asked about something that is 100% in the dead-center of my wheelhouse (e.g., what does Michigan Law like to see in a personal statement?). Weirdly, the proportion of people actually taking my advice (or, at least, pretending to take it) seems fairly constant, irrespective of my qualifications in any given instance—which has led me to come up with a list of three mistakes people make when it comes to advice.

- Mistake One: not asking for advice

- Mistake Two: asking the wrong people for advice

- Mistake Three: not taking good advice

Mistake One is kind of cut and dried. Sometimes you want to puzzle something out on your own, and that’s fine. But if you find yourself in a prolonged struggle about what to do or how to do something, you should probably cast about for some external help. Two heads = better than one, etc. etc. etc. Speaking from personal observation, I will note that you are always free to ignore advice you don’t like, so why not take the plunge?

Mistake Two is a little trickier. Who is the right person? You could just crowd-source it, on the grounds that the right answer will make itself evident by dint of volume. I’m not a fan of this method, because it means you’re probably going to catch up in your net some people who are themselves terribly misguided, or have an agenda that is at cross-purposes with your own, or are reluctant to tell you what they think you may not want to hear. A majority-rules answer might have nothing to do with some larger truth if you have enough examples of any or all of these advice-giving variations in your pool.

Let me come up with a random, purely hypothetical consider-the-source example involving a high school senior who may or may not live in my house. Suppose that person wants to take physics and the school website says that calculus, which that person is not taking, is either a pre- or co-requisite for physics. How to determine how seriously to take this edict? That person could ask his mom, who has a job in the field of education and who loves him dearly and who has been heavily invested in his happiness and well-being for 17 years. Or he could ask some other high school kid. I think you know where this one is going. Well, actually, in my hypothetical example, the high school senior asked both people. He simply chose to ignore the mother’s advice (take calculus) and to instead act on the other high schooler’s advice (NBD). That’s cool. That’s fine. I hardly even mind anymore. I mean, it’s not about me. I know this. Really, I do know this.

But that brings us nicely to Mistake Three, the trickiest of all—evaluating the advice and figuring out whether to take it. Well, technically, maybe we’re still at the Mistake Two stage: When you’re figuring out whom to ask, in addition to asking someone well-informed, make sure you ask someone with whom you don’t have other, say, “issues” that might make you irrationally unwilling to take the advice. Right? I can’t be the only person who knows the somewhat shameful feeling of hearing what is clearly good guidance from someone whom, for whatever reason, you have a tendency to impose some kind of mental deduction. “Yep,” you say to yourself. “That makes sense. And yet, no.” Now, sometimes this is a totally valid reaction. Hell, you know yourself and your circumstances better than anyone else, and so you have to be the one to decide whether advice truly makes sense. But when you feel yourself reluctant to take seemingly sound advice, you need to take a step back and reconsider. Maybe your reluctance is telling you something significant and valid. Or, maybe you’re just being an idiot. Try to ask someone who you really trust, to avoid that whole problem.

But okay, I’ve been blabbing in generalities for long enough. Let me try to give this post some patina of relevance and talk about law school admissions. Try this one: You applied to law school in a prior year and didn’t get in. You want to reapply. Whom to ask for help? Arguably the least useful source is the commonly employed one of asking a bunch of strangers online; they will likely be some combination of well-intentioned but imperfectly informed along with imperfectly informed and weirdly hostile.

I recommend the direct course. (See what I did there? Giving advice! Again! Unasked!) Ask a law school admissions officer or a pre-law advisor, or, ideally, both. The admissions officer has the advantage of being the horse’s mouth, as it were, and the pre-law advisor, while one step removed from admissions, has the probable advantage of having talked to lots of horses.

The pre-law advisor also has the considerable advantage—or at least, potentially has this advantage—of actually knowing you. This gives the advisor the edge over the admissions officer, in most cases. Usually when I’m being asked for advice by applicants, it’s at a stage in the process when I’m relatively, or wholly, ignorant about their situations. As a result, it is hard to be entirely confident that I’m giving sound advice. Likewise, it is a lot easier to give frank (and therefore useful) advice when you have an established relationship with someone. (One student and I have a long-running debate about whether you ought to tell someone when they have something stuck in their teeth, but however you come out on that question, it is clearly less stressful to do that with someone you like and who knows you like him or her.) Finally, I’ll note—the prelaw advisor’s principal mission is to help you get into law school. He or she is acting as your advocate—your lawyer, if you will. The law school admissions officer’s mission, on the other hand, is to put together a class for the law school; the admissions officer is acting, in essence, as a judge. Depending on the nature of your question, therefore, there might be a conflict of interest in getting lawyerly advice from the admissions officer. (But you can trust my advice! I swear!!)

For all these reasons, if you have a prelaw advisor you can call upon, that is the best place to start. There are a lot of great prelaw advisors out there. (When I first wrote that sentence, I was tempted to start listing the all-stars I know, but it got to be a ridiculously long list, and therefore irritating to read, so I’m skipping it.) In fact, I have a lot of prelaw advisors come to me with questions from their advisees, and that is probably my favorite advice-giving format. Having my advice be mediated by someone else, who has an established relationship with the person who needs the advice and can present it in a tailored and appropriate way, is the best of all possible advice-giving worlds.

The second-best advice source? A meandering, free-styling blog, of course.

But remember: Ultimately, the control is in your hands. So if someone tells you your dreams are stupid? Take my advice, and seek a second opinion.