Expanding access, enhancing education

This week, the U.S. Supreme Court is hearing argument in the case of Fisher v. University of Texas, and so tackling for the second time in a decade the question of affirmative action in higher education. The decade saw its first examination of the question in 2003, with the University of Michigan’s vigorous defense of two different admissions policies: one in use at the Law School, upheld in Grutter v. Bollinger, and one in use for undergrad admissions, struck down in Gratz v. Bollinger. Combined, the Court’s two opinions stand for the proposition that the University has a compelling interest in pursuing racial diversity in the student body, but that to do so, the admissions policy must be holistic, treating race in a nuanced way, as one of many factors. Just a few years later, the Law School rewrote its policy despite the Supreme Court victory, because Michigan voters—as those in several other states—passed “Proposal 2” (not Proposition—that’s California’s terminology), a ballot initiative prohibiting public universities from “grant preferential treatment to … any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of … public education.” So, now our admissions policy, while broad and holistic, is race-blind. We are required by federal law to collect race data, but the page with that checkbox is removed from the application file until after a final decision has been reached. While applicants may very well write about race or ethnicity in their essays—as people frequently do about religion, disability, family status, and a host of other background characteristics that do not serve as the basis for admissions decision—we do not treat race qua race as a factor.

One thing we do treat as a factor, though, is socioeconomic status. Although the term “diversity” is frequently employed as being coterminous with racial diversity—by both detractors and proponents of affirmative action—it of course actually means almost the opposite: a multiplicity, a variety of traits. We care a lot about academic background, for instance; EE degrees and classicists provide needed enrichment; math majors tend to think about problems in ways wholly different from art history majors. We care about rural backgrounds and urban backgrounds—one recent great admit had the kind of urban upbringing where she had never seen stars in the night sky until college, and I’m hopeful she had some interesting discussions with that class’s fourth-generation rancher. We care about viewpoint diversity, because there is nothing so boring as a conversation about a legal issue that is also an au courant political hot potato where every single person in that conversation thinks the same damn thing; we want the lovers of Limbaugh and the minions of Maher. And so forth.

Now, socioeconomic status, or class, has been advanced by some as a substitute for racial diversity: schools are urged to eschew race and rely instead on class as the sole factor for attaining “diversity.” But the two criteria do not stand in opposition to each other; in the absence of a Prop-2-style prohibition, a school might well choose to profitably employ both factors simultaneously, as information worth considering about an applicant, to attain two wholly different types of diversity. It is worth noting that class diversity doesn’t ensure racial diversity: There are many more poor whites in this country than there are poor people of any other race, and taking socioeconomic background into account is not an effective proxy for taking race into account.

In other words, considering socioeconomic status as a factor in admissions is a worthy undertaking completely irrespective of whether a school considers race. A number of rationales underlie that claim; two of the most common are aptly summed up by Michigan Law alumna Angela Onwuachi-Willig, ’97, writing with Amber Fricke in Class, Classes, and Classic Race-baiting: What’s in a Definition?, 88 Denver University Law Review 807 (2011):

A number of the arguments asserted in favor of racial diversity in Grutter v. Bollinger also may apply to class diversity. For example, just like racial diversity, class diversity among students can contribute to a robust exchange of ideas on legal issues. Additionally, to the extent that law schools represent the training ground for a large number of our Nation’s leaders and to the extent that we want to cultivate a set of leaders with legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry, class diversity, like race diversity, may signal to all citizens that the law school path to leadership is open to people from a broad range of class backgrounds.

Certainly, class is a quite salient self-defining factor, just like race. I have heard many reports over the years from students that indicate they are extremely aware of their class in relation to that of other students; indeed, this intuition has been borne out by explicit discussions during the Law School’s MAP pre-orientation program. Like race, class background is often felt as a taboo point of discussion—indeed, because in the very resource-rich environment of the Law School, class background has a way of becoming less apparent, more invisible, students have frequently reported to me that they are sometimes less willing to talk about their family income or class background than they are to talk about their race.

So the logic for having a “critical mass” of people from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds is important for the same reasons that have been articulated in support of having a critical mass from different races. Faculty frequently report that classroom discussions are best with students from a wide variety of backgrounds; the lens through which students view and interpret the law varies considerably based on their upbringing, particularly with regard to assumptions students make about those whom the law affects. But that only works if those with the diverse backgrounds express their views—and the likelihood that that will occur when the background is one to which any discussion taboo attaches, like race and class, is significantly enhanced when there are others in the classroom who hail from similar backgrounds. Finally, having a “critical mass” of people from any given identity group means that there are far more likely to be differing opinions within the given group; that is, the discussion will not only benefit from the voices of people from some particular background, but will be more nuanced– enhanced by differing viewpoints within and between backgrounds. A range of participants helps to eliminate the wrong-headed perception that there is a “black point of view,” or a “working-class point of view.” The concept of critical mass aims for both diversity of viewpoint and diversity of experience.

In any event, as a public institution, there are good reasons why this Law School in particular should be committed to looking for ways to expand access—and one effective way of doing that is considering class as an element in the admissions process. And in fact, we have long done so. When I revised the Law School’s application for the 2002-2003 admissions season, I included a question asking about the educational level attained by the applicant’s parents. (I did so, I should hasten to add, not because this very good idea came into my own head full-blown: I simply had the sense to take the suggestion of the excellent Beth Wilner, an assistant director who overlapped with me very briefly right after I began in Admissions at the end of the 2001 season.) Earlier iterations of our application asked about parental employment, but the answers there were unreliable: often ambiguous, not infrequently entirely blank, and simply not consistently giving us the information we were seeking. Knowing parental education levels would be a far more effective tool for insight into socioeconomic background, we believed, and so, beginning with admissions decisions made the year prior to the issuance of Grutter, we added it to our panoply of considerations.

To be sure, the question is only an imperfect proxy. Some people with high school educations go on to have great economic success, and the children of those people haven’t had to grapple with serious socioeconomic disadvantage. The best mechanism for assessing socioeconomic background would be detailed family financial information. An admissions office’s desire for lots of information, though, has to be balanced against an applicant’s reasonable interest in some degree of privacy. And it didn’t seem like a good recruiting gambit to make filling out the application seem a whole lot like filling out a tax return.

We didn’t begin tallying the data elicited by our new question until a few years after we started asking it. Why the lag? For one thing—fun admissions fact!—a not insignificant portion of each class has been deferred from a prior year; that means that for the first couple of years of collecting any new datum, we have an imperfect dataset as people from prior years’ admissions processes get rolled into the group. But honestly, I think the principal reason I didn’t count it up is that I just didn’t think to. There are many bits of data that we have to report to the ABA, and there are many other bits that people ask me about (“How many people graduated from my alma mater?” is a biggie, as is, “How many classics/physics/history/econ majors do we have?”). But no one ever seemed to ask about measures of socioeconomic diversity—in part, I imagine, because other law schools don’t seem to collect the information (although a number of colleges do), and so it just hasn’t been a standard part of the dialogue about law school admissions—and it did not immediately occur to me to expand my universe of computations.

But even after I realized that this information would be at least as interesting and useful to track as, say, the number of Fulbright recipients, I didn’t really do anything with it. I would include it in my annual here’s-the-class email to the Law School faculty and staff, and there it languished.

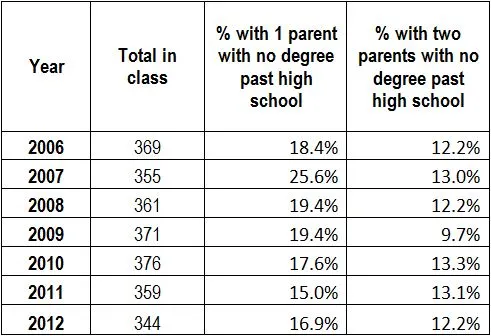

Let it languish no more! As the table below shows, roughly a third of our students have at least one parent without a degree beyond high school, and a third to a half of that group comes from a family where neither parent has a degree past high school. The data are consistent across both admissions regimes—that where race was a factor in admissions, and that where it was not. Enjoy.

-Dean Z.

Senior Assistant Dean for Admissions,

Financial Aid, and Career Planning